When I was looking for my first teaching job over 20 years ago, administrators repeatedly told me that as a history teacher I wouldn’t get hired unless I also coached or taught English or science.

They said, “We don’t test history,” and “Anyone can teach history, so we have coaches do it,” and “No one uses history or civics.” History and civics education were neglected and sometimes even scorned.

Our country is now paying the price for such mistaken attitudes.

In Alaska, we’ve started to update the Social Studies standards, but is has been over 20 years; other core content areas have been revised in the last five-to-seven years.

The need is urgent. As Educating for American Democracy, an in-depth, wide-ranging effort that explored opportunities to improve civics and history education, states, “We as a nation have failed to prepare young Americans for self-government, leaving the world’s oldest constitutional democracy in grave danger, afflicted by both cynicism and nostalgia.”

Advocates also point out that federal spending per pupil in history and civics averages $0.05, whereas STEM education (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) per pupil averages $50 — a thousandfold difference in funding allocation.

However, legislation to increase federal investment in civics education is generating bi-partisan support in Congress. The “Educating for Democracy Act,” recently introduced in the U.S. Senate, would invest $1 billion to broaden access to and strengthen civics and history education from K-12 through higher education across the country. The legislation would provide grants to states, non-profits, institutions of higher education, and civics education researchers.

I’m hopeful we can reinvent American representative democracy and be closer to the promise of a more perfect union for all Americans, not just a few. One

States should adopt the Educating for American Democracy framework into their standards. This approach focuses on shifting from breadth to depth, cultivating civil disagreement and integrating multi-year civics programs. While a great deal of districts still need to make this move, many educators like me are already integrating elements of the framework.

However, this ad-hoc approach to updating standards leaves gaps for which students receive quality civic education.

Too often, under-resourced schools or ones that serve students from diverse backgrounds don’t teach civics because they lack time, resources and skilled staff; this means students who are marginalized the most are further disenfranchised.

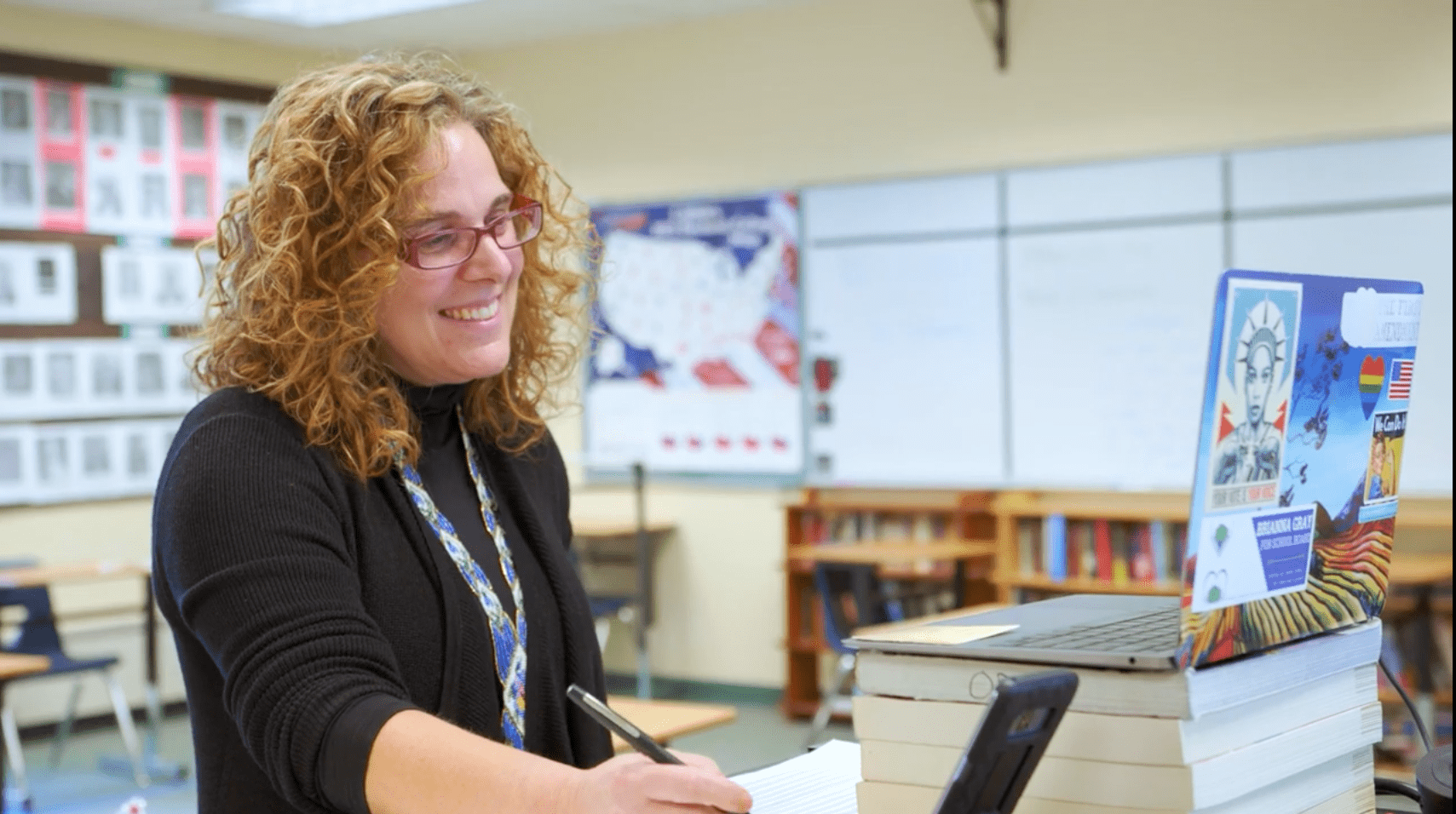

One way educators can be effective on this front is by leveraging today’s news events to help students make sense of the present and past. The last 12 months have given us more material to work with than we could have ever imagined.

In January, we saw a coup in Myanmar and, in the U.S., the insurrection at the Capitol and the subsequent impeachment trial. I used these events to help my world history students evaluate factors that need to be in place to have a functioning and healthy democracy. Essentially, students explored why Myanmar had a coup but the U.S. was holding an impeachment trial.

The students applied media literacy skills and read articles from varying perspectives; they defined representative democracy and started the lesson by analyzing historical quotes. They connected the events in Myanmar to self-determination movements and students explored the challenges of self-government after the end of colonial rule.

They compared the U.S. Constitution and the Myanmar Constitution and identified differences, which allowed them to compare the response of election fraud allegations in Myanmar with the response in the U.S. and answered the question “Why wasn’t there a coup in the U.S.?”

My goal was for students to understand the basic “who, what, why” from a balanced perspective and then to evaluate and discuss the broader issues of rule of law, the role of imperialism, power, and oppression, and the elements of a healthy democracy — not for them to debate “Should the president be impeached?”

As scholars, my students should be studying the events using context to then assess the situation and decide.

Most importantly, we didn’t debate issues like the impeachment trial — there were no winners or losers — that would promote partisanship on a topic that’s already highly partisan. We discussed the issue, we explored and learned to gain a deeper understanding of our ideas and the ideas of others in order to inform our decisions as residents of a representative democracy.

The cornerstone of deep civic learning is establishing a brave classroom environment. I have a classroom contract built collaboratively with students; because we have a foundation of civil discourse, we can have hard and intense conversations. We disagree with ideas, not people, and we ground our discussions using fact-based evidence from peer-reviewed and credible sources.

This all gives me hope that we can gather our allies at school and in the community and seize this moment to transform our standards and curriculums to be what our students deserve, to help “heal the heart of democracy” and save the republic.