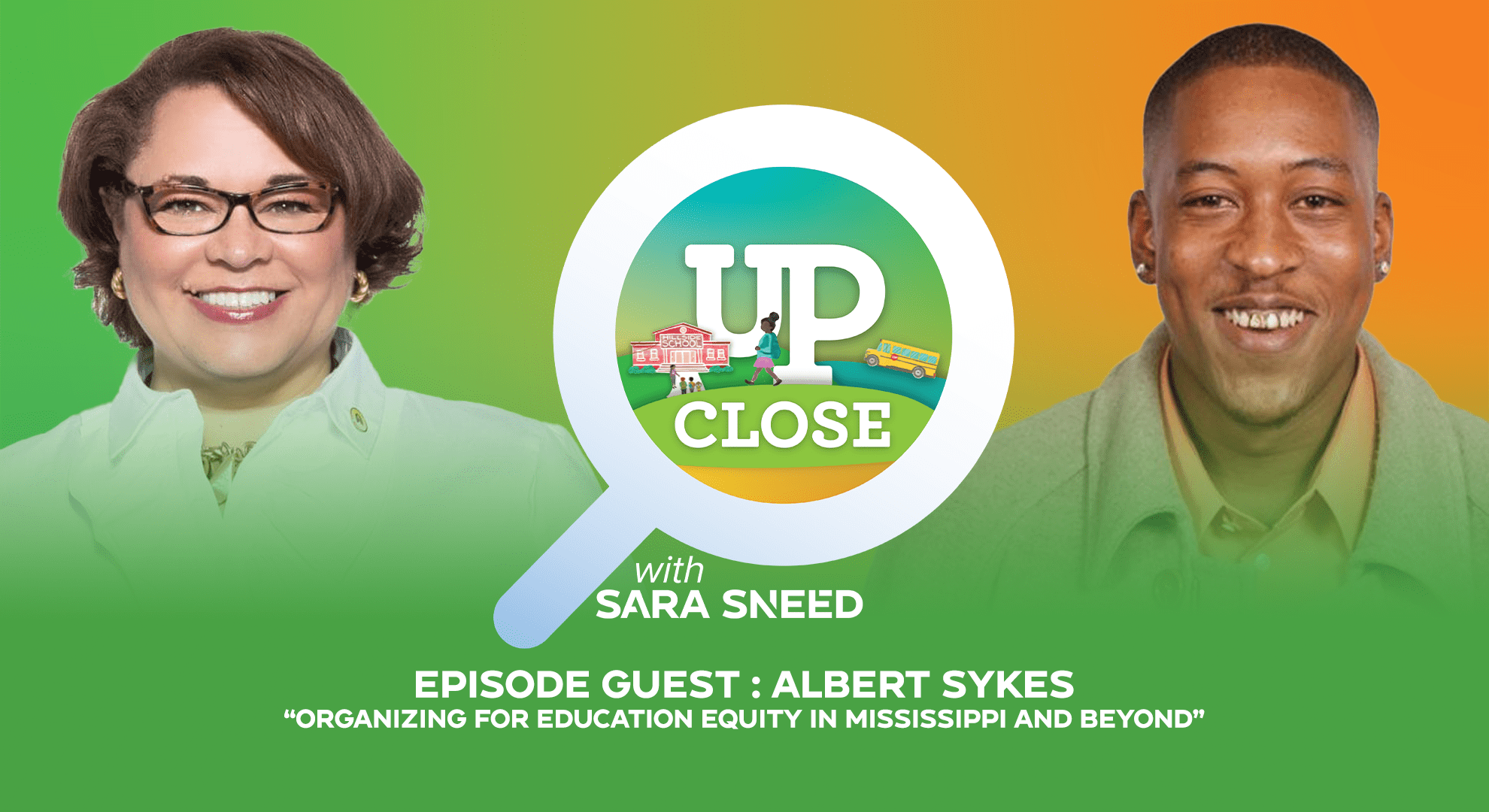

In the latest episode of the Up Close Podcast with Sara Sneed, Albert Sykes, executive director of the Institute for Democratic Education in America, discussed how being introduced to activism at a young age helped set him on a path of lifelong advocacy for civil rights and education justice.

The conversation begins with Albert recounting the day that he learned about Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rosa Parks in his kindergarten class. When he excitedly told his grandmother what he had learned—that these were Black people who had changed the nation because of what they stood for—she told him that his home in Jackson, Miss., was only one street away from the home of another famous civil rights activist.

That was how Albert learned about Medgar Evers, an advocate for voting rights, desegregation, and economic opportunity for Black Americans. Evers was assassinated in 1963 at his home, in the same small community of Jackson where Albert and his family lived.

“What I learned was the difference between sacrifice and thievery. That people dedicated their life to a cause, but their life was stolen from them because of their dedication to that cause.”

Albert went on to meet a number of other civil rights advocates as an adolescent and young adult, many of whom mentored Albert and helped him understand how the movement for Black civil rights in Mississippi fit into movements happening across the country.

It was in this context that Albert decided to dedicate his life to the fight for justice, equity, and opportunity in America.

“When I started absorbing those stories, I started to understand that these were not just stories, these were places of accountability, of what I owe back for the things that have been paid for in front of me. And when I’m hearing it firsthand from the people who paid it forward, I started to understand what I had to do and what I needed to do.”

When it comes to education justice, Albert explains how access to a high quality education is a right that is denied to certain communities, and how community engagement can be the key to addressing the unique needs of different schools.

The community schools model, which The NEA Foundation has supported in Jackson in partnership with local leaders and organizations, does not assign blanket solutions to under-resourced schools. Instead, the equity-based approach works with organizations, school leaders, and families to serve students and families in the ways that work best for them, whether that’s providing physical or mental health services, organizing after-school tutoring, or scheduling home visits. The goal is to provide the conditions in which schools and communities can thrive, all with the power of community partnerships.

“It’s a beautiful struggle,” said Albert about the community schools model. “It’s been this place of trial and error, but it’s also been a place of honesty and healing, where people can see that sometimes we have to disagree on our way to getting it right. It don’t have to end our relationship. If we started off with the children in the center, then we’ll finish with the children in the center, and we’ll be more proud of the product that we went through the fire together to get than the one we could’ve just dropped.”