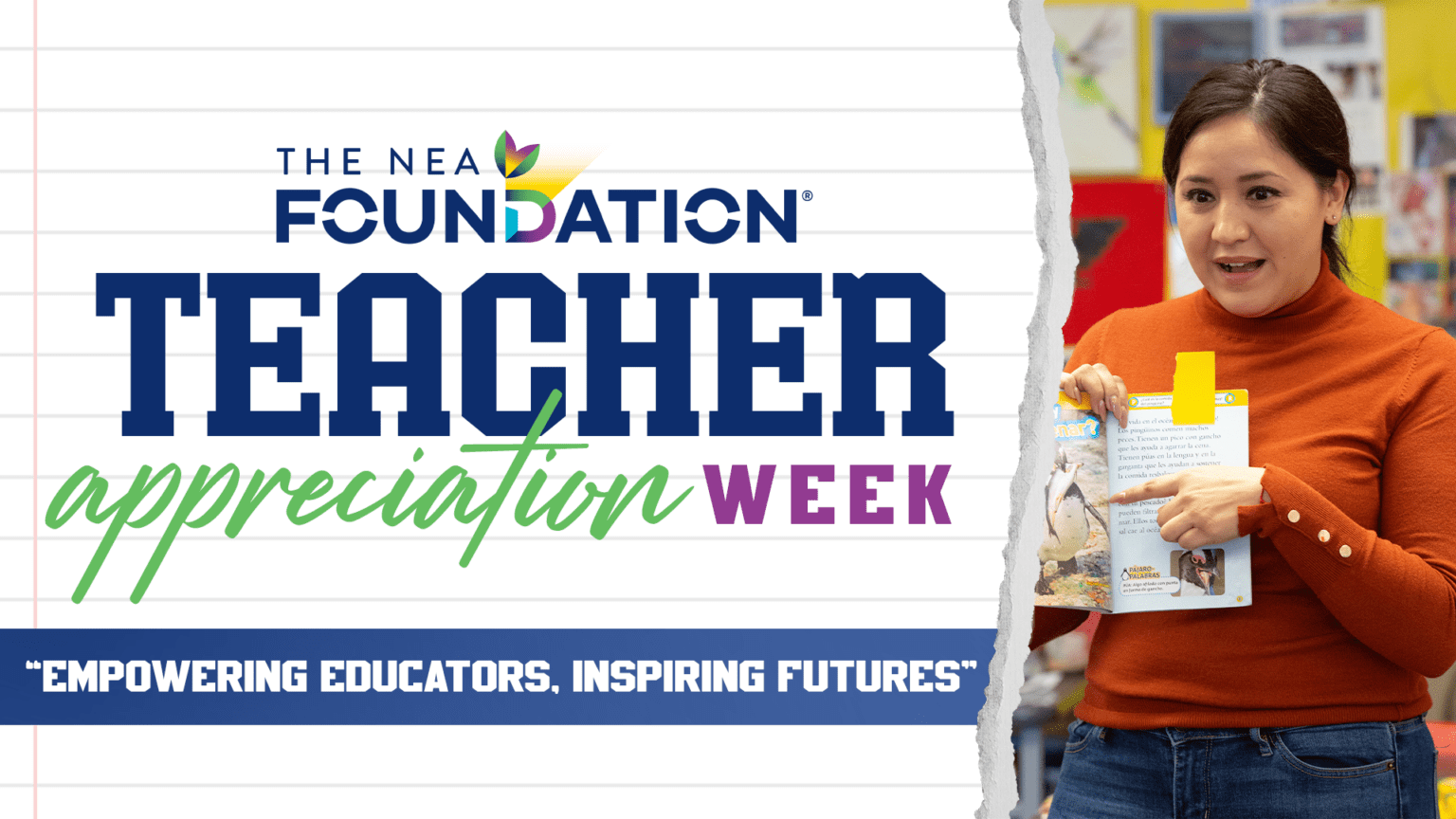

Maribel Vilchez is a third grade educator at Lydia Hawk Elementary School in Lacey, Washington. She is also one of the five educators receiving the 2025 Horace Mann Awards for Teaching Excellence.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve heard the same messages. A narrative that intentionally or unintentionally undermines and dismisses people.

“It’s different!”

“You don’t have to understand it, let alone do it their way. It just is! Move on!”

… and every time I encounter this message, I cannot stop feeling uneasy and quite uncomfortable.

It seems the message is, “That is THEM, and this is US,” perpetuating an invisible line of division. It’s an unspoken way of creating different spaces where people can coexist, but not be together.

So inevitably, I ask myself, as so many others ask themselves: Where am I? Am I in the “US” space, where I am included, where I am accepted? Or am I in the “THEM” space, where I am implicitly pushed aside and excluded? Or perhaps I am in the “US” space, but only if the unknowns I bring do not provoke change or challenge the way things are always done.

Being an immigrant from Peru and living in the U.S. for more than two decades, I have often found myself in the “THEM” space. In those moments, sometimes I tried to explain myself. Other times, I tried to infer the roots of people’s actions to understand where they were coming from. And sometimes, I just felt emotional because I was being othered.

While othering may be a natural behavior stemming from human evolution — grouping people into categories—it is counterproductive to the idea of an inclusive society, one where everyone has a place, where everyone has a voice, and where everyone is present in the “US” space.

The idea of othering brings back memories when my heart felt torn, and I felt invisible. In group conversations about music, sports, or traditions—things often unfamiliar to me—I tried to embrace the newness, but it was always one-sided. What I knew or cared about seemed irrelevant or nonexistent. Human interactions can often become instruments of exclusion, leaving others feeling minimized and broken. We all need doses of empathy.

Empathy: the ability to sense other people’s emotions, coupled with the ability to imagine what someone else might be thinking or feeling. – Greater Good magazine

Our schools are places where students, families, and staff come together, with our differences making our community unique. When I think of classroom communities, I envision faces of children and adults who genuinely feel valued. Each person brings unique traits and experiences that shape who we are, and when we uplift each other by embracing these traits as assets that benefit us all, we foster a stronger community. This comes through openness, through listening, and through genuine communication with a desire to truly understand and accept one another. This is when we become us and truly become a community.

However, even in our school communities, we don’t always understand one another. I recall one after-school event where children were running around freely, to the amusement of some adults but the frustration of others. It didn’t take long for some teachers to get upset with the parents, accusing them of not disciplining their “wild” children. Comments like, “Those children behave like that because their parents don’t care!” surfaced quickly.

At the same time, these children’s parents were wondering why the teachers weren’t doing anything to control the children in *their* school. Here lies a cultural difference. A couple of weeks later, in conversation, we learned that many of the parents at the event, who had Guatemalan backgrounds, believed that when their children are at school, it’s the teachers’ domain. Out of respect for teachers’ authority, they do not intervene, thinking that doing so would undermine the teachers.

This is just one example of how differing viewpoints can easily other a minority group, even when both sides have the same goal. Communication, voice, and, more importantly, empathy play critical roles in bridging our differences and bringing us closer together.

As an advocate for linguistically and culturally rich communities, I firmly believe that our students are invaluable assets who can enrich our teaching. My students’ linguistic and cultural backgrounds allow me to broaden my knowledge and understanding of the world, benefiting our entire classroom community. When students see themselves represented in our learning, they feel a sense of pride and belonging. This is when we become Us.

Empathy and inclusion are crucial. I urge us to look beyond our own cultural beliefs and seek to understand those of others. In doing so, we can find our commonalities and, rather than “othering,” begin to truly humanize each other.

“I have come to the frightening conclusion that I am the decisive element. It is my personal approach that creates the climate. It is my daily mood that makes the weather. I possess tremendous power to make life miserable or joyous. I can be a tool of torture or an instrument of inspiration, I can humiliate or humor, hurt or heal…” – Haim Ginott

THE NEA FOUNDATION IS COMMITTED TO FEATURING DIVERSE VOICES AND PERSPECTIVES ABOUT CRITICAL ISSUES FACING PUBLIC EDUCATION, STUDENTS, AND EDUCATORS. THESE VIEWS DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THOSE OF THE NEA FOUNDATION.